Does roof ventilation work?

Before we answer the question of “Does roof ventilation work?” let’s talk about insulation.

Believe it or not, the ancient Egyptians pioneered insulation using asbestos—a decision we now know was far from ideal. Fortunately, insulation has evolved significantly, becoming safe, affordable, and easy to install. Insulation works primarily because it traps air; but for this effect to work, the air must be still.

Why Roof Ventilation Fails for Cooling Homes

Despite the intent to control mould and extreme heat by connecting indoor spaces to roof areas, this approach is flawed for several reasons:

- Non-Powered Roof Ventilation: Moves an insignificant amount of air, a rarely acknowledged detail.

- Mechanical Roof Ventilation: While more effective in air movement, it introduces season-dependent problems.

Greater Importance Lies Elsewhere

- Ceiling Airtightness and Insulation Consistency: Far more crucial for heating and cooling. Pre-insulation, methods like whirly birds offered value during summer, but with modern insulation, these are rendered ineffectual.

Counterproductive Outcomes of Roof Ventilation for Cooling

- Hot Air Influx: Using indoor air to feed ventilation devices draws in hot summer air through windows, doors, and leakage points, overwhelming air conditioning systems.

- Humidity Concerns: Excessive uncontrolled ventilation leaves homes as susceptible to mould as airtight, non-ventilated ones. Effective solutions include humidity-sensing bathroom fans with door vents (leveraging whole-house air leakage) and externally vented kitchen range hoods for rapid humid air removal.

Practicality and Seasonal Drawbacks

- Maintenance Risks: Manually operated ceiling vents require risky ladder access, especially for the elderly, and may not seal airtight when closed.

- Winter Moisture: Roof ventilation devices fail to adequately address moisture from bathroom fans and kitchen hoods if not directly ducted outside through tiled or metal deck roofs, leading to roof cavity issues.

- Pollen Infiltration: Indoor ceiling ventilation with roof devices can increase indoor pollen, exacerbating hay fever and asthma.

Before insulation became commonly used in Australia, old roof ventilation devices used to have fans inside them, but nowadays most versions do not. In homes/sheds that have no ventilation and insulation, a roof ventilator could make a difference especially if it is motorised. But in today’s modern age of insulation in residential homes, they are no longer viable in the majority of climates. If you wanted to ventilate a roof cavity right, ridge cap ventilation, along the whole ridge is capable of moving much more air with a much larger surface area opening. For surviving the heat, relying on insulation and air tightness is a much more logical way to go, especially in places where temperatures can drop quite low at night or during the winter period.

Table of benefits

| Winter | Summer | |

|---|---|---|

| No insulation with ceiling/wall ventilation grills in the plaster | Not Beneficial. Brings uncontrolled cold air inside from outside. With a colder ceiling surface, more energy will be used to warm the house. | May be beneficial, occasionally depending on your climate. |

| No insulation with "NO" ceiling/wall ventilation grills in the plaster | Not Benefical. With a colder ceiling surface, more energy will be used to warm the house. | May be beneficial occasionally depending on your climate. |

| Insulated ceiling with ceiling/wall ventilation | Not Beneficial. Brings uncontrolled cold air inside from outside | Does not work effectively |

| Insulation with no ceiling/wall ventilation | Not Benefitial | Does not work effectively |

| Windy | Not Beneficial. Brings uncontrolled cold air inside from outside | Brings uncontrolled hot air inside from outside |

Beware of advice to install ceiling vents feeding hot air from living areas into roof areas for expulsion via roof ventilation devices. These can:

- Unsarked tiled roof may introduce positive pressures from wind or expanding hot air, drawing ventilated air back into the home.

- In winter, result in a colder roof area, negating potential thermal gains (though insulation mitigates this benefit anyway).

Table of hot hours compared to cold hours in a year.

| Country | the amount of hours with temperatures BELOW 10C | the amount of hours with temperatures ABOVE 30C |

|---|---|---|

| Melbourne | 1336 | 176 |

| Sydney | 331 | 68 |

| Canberra | 3192 | 109 |

| Hobart | 3609 | 17 |

| Adelaide | 1021 | 484 |

| Geelong | 2342 | 155 |

| Woolongong | 583 | 44 |

| Bendigo | 3609 | 109 |

| Brisbane | 342 | 66 |

| Perth | 743 | 471 |

Focus on achieving insulation consistency and airtightness in your building envelope, rather than over-complicating it with the assumption that external air can be leveraged for comfort. In moisture-prone areas like bathrooms and kitchens, prioritise strategic ventilation by carefully planning the exit path for humid air to directly vent outside and the entry point for fresh air.

Special Consideration for roof systems with sarking/sisalation: Roof ventilation can be beneficial here due to inherent airflow limitations, which can lead to moisture issues. However, note that these systems are not designed for cooling. Insulation consistency makes a noticeable difference in comfort.

Insulate right, ventilate right, and then go energy-lite.

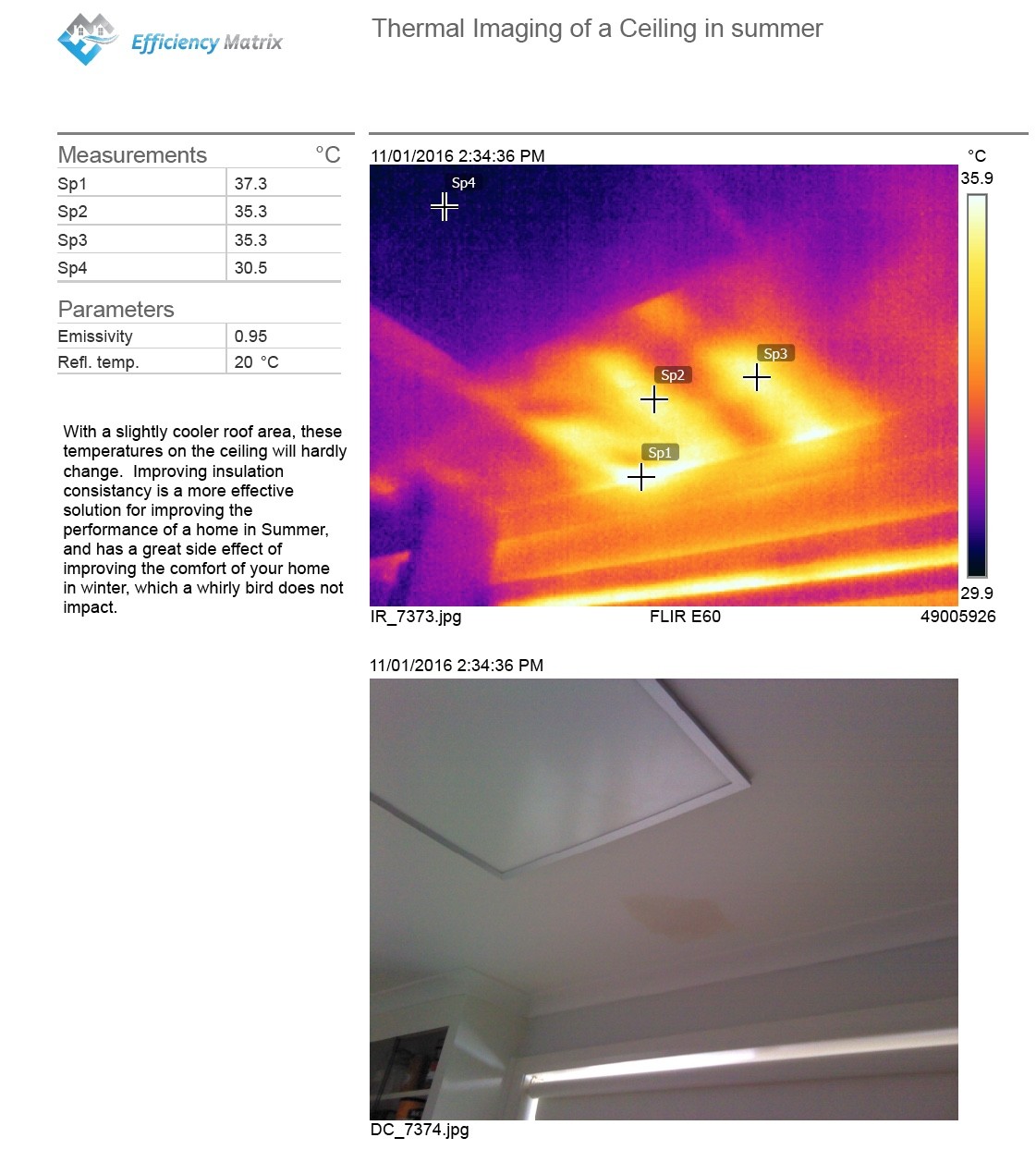

Thermal imaging of a ceiling not insulated properly.

Dr. Mark Dewsbury from the School of Architecture & Design, UTAS, has been exploring many issues around energy flows, ventilation, and condensation within unconditioned and conditioned rooms and roof spaces of Australian homes. The research has highlighted many myths and anti-science beliefs about roof space thermal dynamics.

Mark Dewsbury (Ph.D.) | Lecturer & Building Research | School of Architecture & Design| Faculty of Science, Engineering & Technology

By John Konstantakopoulos